Hey everyone! Today I want to talk about something that’s been bugging me for a while – the Global Interpreter Lock, or GIL as everyone calls it. If you’ve ever wondered why your multi-threaded Python program doesn’t run as fast as you expected, well, the GIL is probably the culprit.

So What Exactly is This GIL Thing?

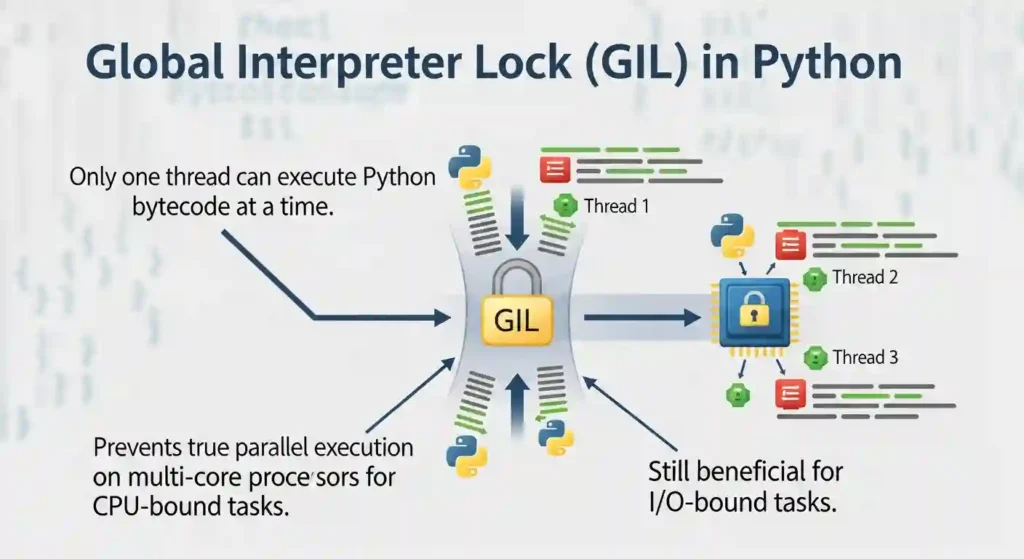

Okay, so here’s the deal. The Global Interpreter Lock is basically a mutex (a lock) that protects access to Python objects. It prevents multiple threads from executing Python bytecode at the same time. Even if you have multiple CPU cores, only ONE thread can execute Python code at any given moment.

Why Does Python Even Have This?

When I first learned about the GIL, my immediate reaction was “Why would anyone design it this way?” But there’s actually a good reason behind it.

Python uses reference counting for memory management. Every object keeps track of how many references point to it, and when that count hits zero, the memory gets freed. The problem is that this reference count needs to be protected from race conditions where two threads try to modify it simultaneously.

The GIL was the simple solution – just make sure only one thread runs at a time, and boom, no race conditions. It made the CPython implementation simpler and actually made single-threaded programs faster because there’s less overhead.

When Does the GIL Actually Slowdown Performance?

Here’s where it gets interesting. The GIL is only a problem for CPU-bound tasks. If your program is doing heavy calculations, processing data, or anything that keeps the CPU busy, the GIL will throttle your performance because threads can’t run in parallel.

But here’s the good news – if you’re doing I/O-bound work (reading files, making network requests, waiting for database queries), the GIL isn’t really an issue. That’s because when a thread is waiting for I/O, it releases the GIL so other threads can run.

I’ve worked on web scrapers and API clients where threading worked perfectly fine because most of the time was spent waiting for responses, not actually processing data.

How I Deal With the GIL

When I need actual parallelism for CPU-intensive tasks, I use the multiprocessing module instead of threading. Each process gets its own Python interpreter and its own GIL, so they can truly run in parallel.

from multiprocessing import Pool

def process_data(chunk):

# Your CPU-intensive work here

return result

if __name__ == '__main__':

with Pool(processes=4) as pool:

results = pool.map(process_data, data_chunks)

The downside? Processes are heavier than threads, and you can’t share memory as easily. But when you need real parallel processing, it’s worth it.

Is There Hope for a GIL-Free Future?

There have been attempts to remove the GIL over the years, but it’s tricky. Removing it would require massive changes to CPython’s internals and could break many existing C extensions that depend on the GIL’s behavior.

That said, there are Python implementations, such as Jython and IronPython, that don’t have a GIL at all. And lately, there’s been renewed interest in making CPython work without the GIL, so who knows what the future holds?

My Final Thoughts

The GIL is one of those things that seems annoying at first, but once you understand it, you learn to work with it. For most of my day-to-day Python programming, it’s honestly not a problem. And when it is, I’ve got workarounds.

The key is knowing what kind of problem you’re solving. CPU-bound? Use multiprocessing. I/O-bound? Threading works great. Once you’ve got that down, the GIL becomes just another quirk of Python that you deal with.